Flint Sit Down Strike (1936-37) – UAW History

The nation is in economic crisis, unemployment is high, people are losing homes, workers are afraid to unionize and families, swamped in debt, struggle for a better life. Worldwide, masses stand up against corporate greed and demand a better quality of life by sitting down and occupying space in a unified effort to be heard. These people — dubbed radicals or even communists by the opposition — believe this organizing movement has critical importance in their effort to create change.

The year is 1936 — not 2012 — a turbulent time for autoworkers whose determination and courage helped the labor movement gain a better quality of life for workers and, ultimately, create the American middle class.

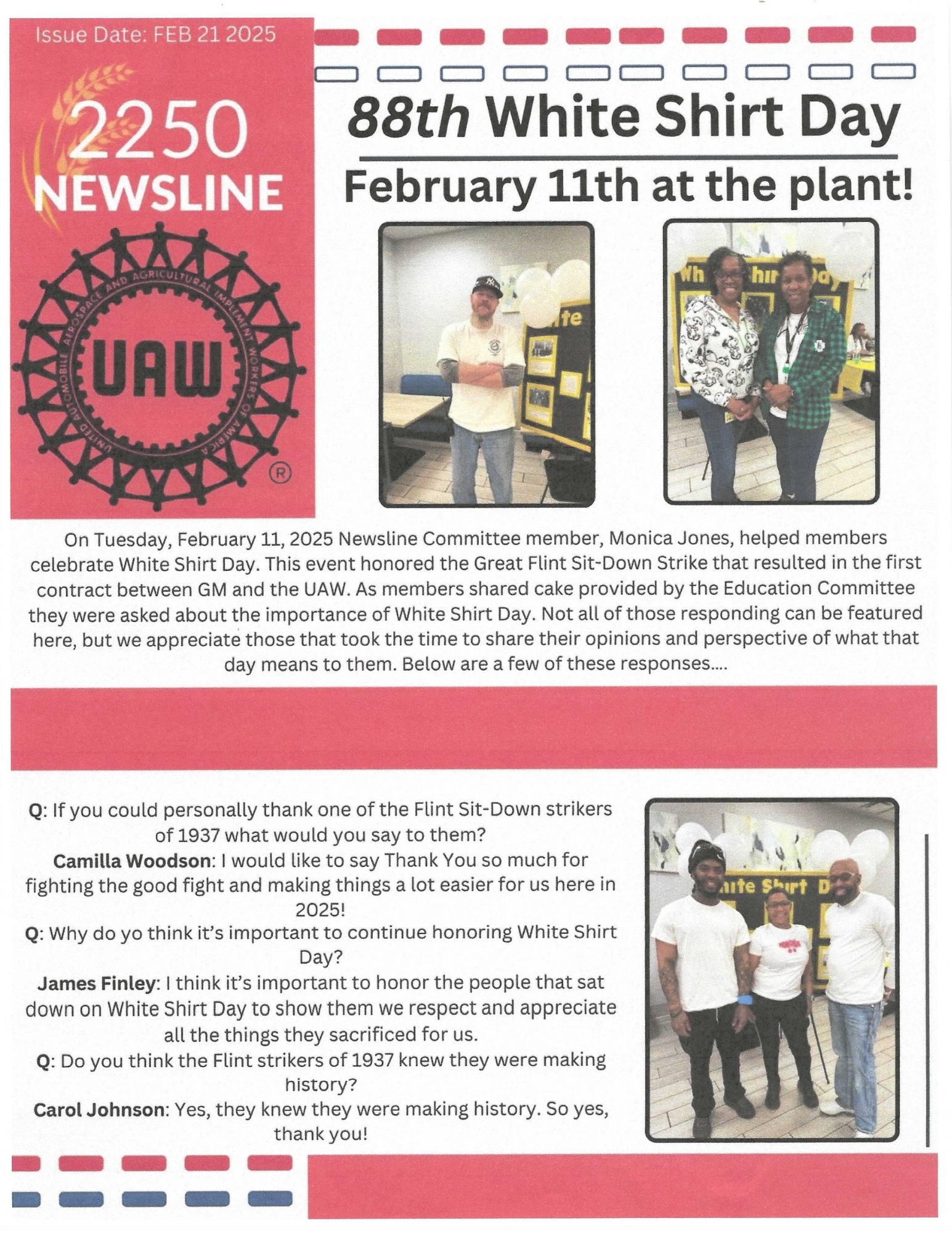

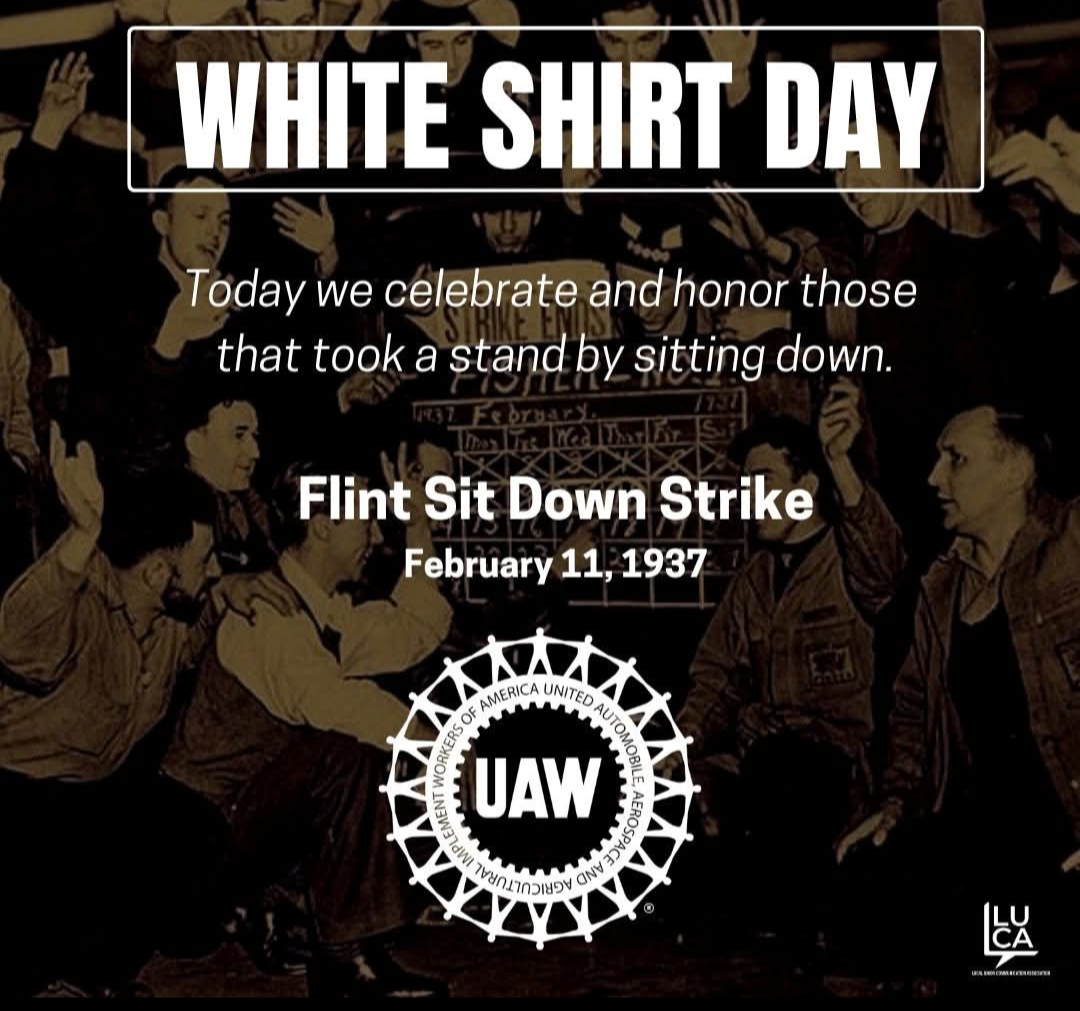

Known as “White Shirt Day,” Feb. 11 marks the 75th anniversary of the most famous of these sit-down actions, the 1936-1937 General Motors Flint Sit-Down Strike. Men and women throughout the UAW wear white-collar attire traditionally donned by management to remember the sacrifices and victories of workers.

But winning was no small task.

“There were people dropping over because of the heat, and other workers were told to step over them,” recalled Geraldine Blankinship, 92, who supported the Women’s Auxiliary and Emergency Brigade when she was just 17.

“They didn’t slow down the line, and they didn’t stop it. They just dragged people away. It was such an inhumane thing to do,” added Blankinship, whose father, Jay Green, was vice chair of the strike. She spent many nights working with her mother, Ida, a red-caped beret-wearing brigade member, who fought bravely to deter the company’s actions.

Workers at GM’s Fisher Plant in Flint, Mich., were tired of fearing not only for their safety, but also for job security, so they initiated a sit-down strike by locking themselves inside the plant for as long as it would take for the company to recognize their right to form a union and negotiate for higher pay and better working conditions. The Flint standoff inspired workers from other GM facilities to sit down in solidarity as well.

The future was unknown for these brave, defiant workers who feared losing their jobs, the threat of police intervention and even of their families abandoning them while they were locked inside.

“I was kind of afraid I’d have to go back to waitressing,” said Pauline Polsgrove, 93, with a laugh. She’s the last surviving female sit-down worker from 1936.

Richard Wiecorek, 95, recalled how “One guy, he had five kids and he’d get so nervous, he’d pass out. He didn’t know if he was going to get his job back.”

The workers’ fortitude would be challenged when police arrived to force them out of the plant, but their spirit and strong community support was too strong to break their drive.

Eventually, something incredible happened to help bring the standoff closer to an end when then-Michigan Gov. Frank Murphy called in the National Guard — to go to the plants and protect workers from police and corporate thugs.

The strike ended after 44 days on Feb. 11, 1937, when GM recognized the UAW and negotiated a first contract. Sit-downers walked out of the plant to find a parade with thousands of supporters.

James Todd, 98, who still teaches square dancing three times a week, was a janitor in 1936 before the strike. Todd is proud of the successes that came as a result of the sit-down movement.

“We all got better jobs … and for black people, we got jobs that we didn’t get before because most of the time, we were just sweeping floors. But after that, we all went on machines.”

In today’s climate, with workers facing corporate-lobbied politicians trying to eliminate collective bargaining rights, Wiecorek has some time-honored wisdom: “If you have a union, hang on to it.”

Video companion piece to the UAW article, 75 YEARS AFTER SITTING DOWN FOR SOLIDARITY, written for the Jan/Feb 2012 issue of Solidarity Magazine by Denn Pietro.

UAW Public Relations Department

All Rights Reserved

Copyright 2012